Debts, Tech and Otherwise

While people debate the validity of "tech debt", others are asking, "What other sorts of 'debt' do we have in software development and delivery?"

09 March 2025

tl;dr A colleague of mine, Scott Porad (CTO, VP Engineering) posted on LinkedIn, asking, "What are all the other kinds of debt like tech debt?" He listed out a few, then asked for others to weigh in, and the list grew... kinda long. And interesting. And made me think about the metaphor more deeply.

His list included financial debt (the OG), Product debt (gaps in the product that impact revenue or lead to support costs), Ops Debt (manual processes performed by the operations team because the software doesn't support the processes), Process Debt (valuable steps of the software development process that are skipped causing quality or velocity issues), and Org Debt (key roles that are not staffed that cause quality or velocity issues).

He then asked others to weigh in with their favorites, and the answers poured in. Many (I won't list them all--partly because I want you to read the original post!) were interesting, and I think they fall into a variety of different categories:

- Technological. Whether it's the data, the UX/Design, the backend, or even the choice to over-depend on open-source without "giving back". Documentation falls in here, too.

- Procedural. What processes are being done by hand that cost the team time, money, or energy? What sorts of things are being hidden by a "lightweight process" focus (a la "agile") because companies are afraid to institute a process, lest they be called "not agile"?

- Mental. What assumptions were made that turned out to be wrong? What assumptions were right "back then" but no longer hold? Is the organization chasing the right problems? What knowledge is missing from the people that need to know?

- Cultural. Any group of humans forms a culture, but is that culture serving the business, or holding it back?

- Talent. A few of the responses mentioned "youth" or "experience" debt, as in a lack of investment into junior talent, or a refusal to recognize the value of experienced veteran talent on the team. Likewise, having "not enough" in raw terms, e.g., understaffed teams.

- Support. This is a more nebulous catch-all category but includes things like "marketing" (neglecting marketing practices over time, leading to damaged brand and customer relationship) or "legal" (failure to recognize the legal and/or regulatory necessities, bringing the company into legal jeopardy).

Again, I encourage readers to go check out Scott's original post. It was fascinating how much of it just poured out in the comments, and the wide-ranging nature of the responses.

Which got me thinking: Are these really "debts"? Or, more to the point, are they bad?

Debt: A Metaphor

If we go back to the original definition of "tech debt", if I remember correctly, I first heard it from Mike Clark back on the NFJS tour in the late 2000s, but Wikipedia tells me that Ward Cunningham first coined the term in 1992 as a metaphor to explain to his boss how making short-term decisions can boomerang and create problems over time, and therefore investment was needed to refactor the code. In particular, the point of the analogy was that "While technical debt can accelerate development in the short term, it may increase future costs and complexity if left unresolved." The official Wikipedia definition of "Technical debt", by the way, is this: "the implied cost of additional work in the future resulting from choosing an expedient solution over a more robust one."

Ward put it like this:

"Shipping first time code is like going into debt. A little debt speeds development so long as it is paid back promptly with a rewrite... The danger occurs when the debt is not repaid. Every minute spent on not-quite-right code counts as interest on that debt. Entire engineering organizations can be brought to a stand-still under the debt load of an unconsolidated implementation, object-oriented or otherwise."

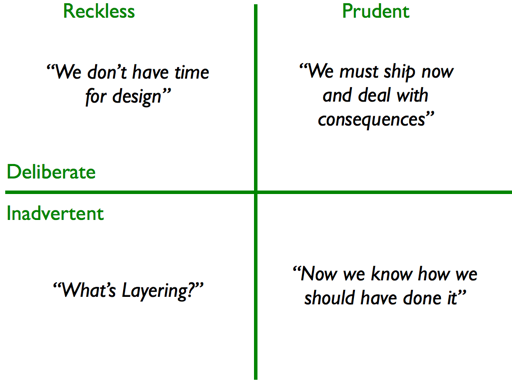

Martin Fowler later wandered into this arena, too, pointing out that debt is sometimes taken on deliberately (a car loan, a mortgage) for good purposes, and sometimes it's accrued accidentally (credit card debt) because of poor planning or execution. He likened it to a quadrant along two axes: reckless vs prudent, deliberate vs inadvertent:

In almost all of the "pain" cases of debt, regardless of the kind, the worst quadrant to be in was Inadvertent/Reckless: We made bad decisions without realizing it, and paid for it later, painfully. Slightly better is Deliberate/Reckless, where we knowingly made a reckless decision (which raises its own questions), and still paid for it later, painfully. The "painfully" part is why most people react so strongly to debt, and to the debt metaphor, and why it often engenders its own kneejerk reactions when the topic appears.

When we look at those list of "debts", pretty much all of them can fit into the definition pretty well: for the subject S, we take on an implied cost of doing additional effort in the future in order to take on the expedient solution now, instead of the more robust one:

- Technological: Data. We take on an implied cost of additional effort refactoring our data and breaking down the silos in order to take on the expedient solution of a denormalized database or maintaining separate independent databases now.

- Technological: Architectural. We take on an implied cost of additional effort refactoring our architecture to be more scalable or more secure or more mobile-friendly in order to take on the expedient solution of shipping a basic three-layer CRUD app now.

- Technological: UI/UX. We take on an implied cost of additional effort building out a more cohesive and coherent user experience in order to take on the expedient solution of shipping a clumsy functional UI now.

- Talent: Youth debt. We take on an implied cost of additional effort mentoring more junior developers later in order to take on the expedient solution of having all senior engineers work on the project now.

- Talent: Experience debt. We take on an implied cost of additional effort building experience in our domain or our systems later in order to take on the expedient solution of severing all the senior engineers on the project now.

... and so on. For each of the topics brought up in Scott's post, there is a very clear sense of "We are taking a short-term view which hurts us in the long run" feeling. And yes, most of us in the IT industry have a story like this (if not several times over) that we lived, and regretted, through.

But I think that's only half the story.

Debt and Evolution/Iteration

The more I go through each of these, the more I realize that there is another idea hiding in here, which is that sometimes we take on the debt because we don't know the future. Think about it this way: Does it make sense to invest heavily into a particular area (application, database, vision, process, talent, ...) if we find that after a few iterations, it's a mistake to take that approach? Think of your favorite startup unicorn story, and how often those unicorns needed to "pivot"--that is, quit what they were doing and try something else entirely different--in order to stay afloat or try something else? If the company hadn't taken the short-term approach, and instead invested a massive amount of time/energy/money into something that was now essentially worthless, all of that investment would now be a waste and therefore a loss.

Or worse, fall prey to the Sunk Cost Fallacy, and become convinced that "They can't give up now!", and fail to pivot entirely.

The truth is, in most practical cases of "debt acquisition", the principals involved in making the decision were faced with the basic conundrum of "Do we ship sooner rather than later, knowing that what we deliver sooner will have some inherent problems with it that will need to be addressed later?" Implicit in this question is the flip side, though, which often helps to present as part of the whole decision-making process: "Do we ship later rather than sooner, knowing that if we wait too long the window of opportunity will close partially or entirely and render the entire enterprise moot?" That "later" part of the question rarely gets uttered out loud, and never gets brought up in the post facto analysis of "We chose the expedient solution n months or years ago, and we got to this point now." Keep in mind, if they chose the long-term solution and failed, we're not around to discuss it! While it's easy to judge the decision post facto, like all decisions at the time they are made, the "right" choice is not nearly so clear. What's worse, we don't have great clarity on the efficacy of the choice here, because we only remember one-fourth of the result quadrant:

| "Debt Results" | Choice: Debt/Expediency | Choice: No debt/"Right" |

|---|---|---|

| Failure result | No data/discussion | No data/discussion |

| Success result | "Agh, the pain!" | No pain to discuss |

In other words, 25% of the squares on the above graph get 100% of the discussion and the angst. Which, by any reasonable interpretation of this data, suggests that the main reason we spend so much time castigating people for making the Debt choice is because that's the only one we talk about.

Debt as a Metaphor

I think, overall, that the debt metaphor works, and works well. It obviously applies to more than just "technical" debt, though, and as Scott's post suggests, there's alot of different kinds of debt we can incur as an organization. Fowler's Reckless-Prudent-Inadvertent-Deliberate quadrant helps categorize the conscious decision around debt, but clearly relies on the individuals involved to describe the differences between "reckless" and "prudent". In the moment, it may feel prudent to be focusing on the here-and-now solution--which, to be fair, it often is, as exemplified by the whole YAGNI (You Ain't Gonna Need It) movement of the agile mindset--and only later does it feel reckless. But that sort of post facto analysis is itself a privilege, because it means we've had the success thus far to be able to go back and reflect on those decisions and attempt to recover/refactor them.

Or look at it this way: How many of us would be perpetual renters had we not taken on the mortgage to buy our first home? How many people could actually get to the point where they had $500k, $1m, or even more, saved up in a bank, waiting to buy the home outright? Debt in of itself isn't bad; it's when it's Inadvertent/Reckless debt that we find the angst.

Tags: management engineering design